Prostate cancer remains one of the most common cancers affecting men worldwide, with the American Cancer Society estimating about 299,010 new cases and 35,250 deaths in the United States alone in 2024. Despite this prevalence, it often evades early detection. For many, a diagnosis comes only after the cancer has reached an advanced or metastatic stage (Stage IV), when treatment options become more limited and outcomes less favorable.

Why Prostate Cancer Is So Hard to Catch Early

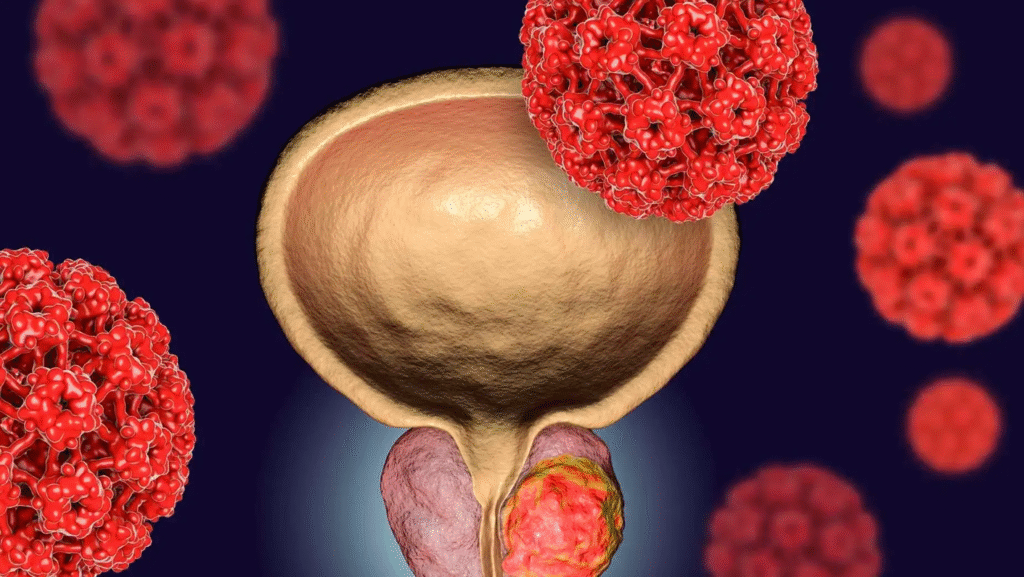

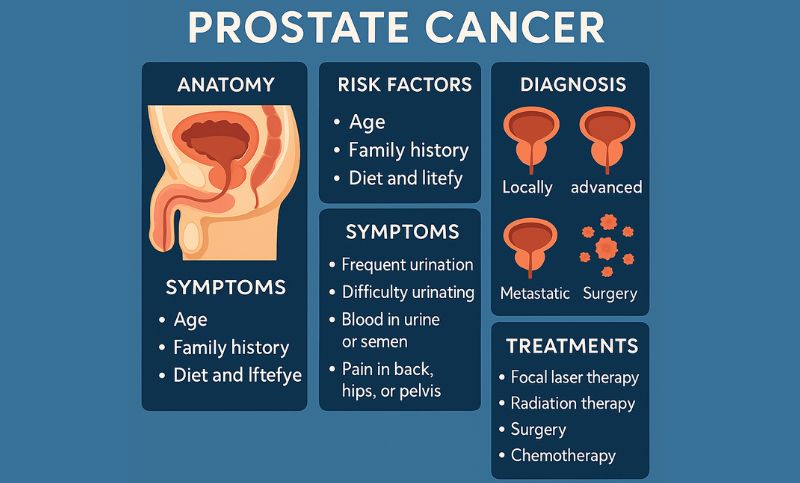

The prostate is a small gland tucked deep within the male pelvis, which makes direct examination difficult. Unlike some cancers that cause noticeable symptoms early on, prostate cancer typically develops silently. Early-stage prostate cancer is often asymptomatic, and when symptoms do appear, they may mimic benign conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or prostatitis.

The standard screening tool, the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test, has limitations. PSA levels can rise due to non-cancerous causes, leading to unnecessary anxiety and biopsies. Conversely, some men with prostate cancer have normal PSA levels, resulting in false reassurance. Digital rectal exams (DRE), another common screening method, are also limited in sensitivity.

This diagnostic gray zone is one reason why many men—approximately 17%—are diagnosed only when the cancer has already spread beyond the prostate.

Interpreting PSA Correctly

PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) is a protein made by both normal and cancerous prostate cells. Understanding PSA is less about one number and more about how it changes over time and context.

1. Absolute PSA Value

<4 ng/mL: Generally considered normal, but aggressive cancers can still exist.

4–10 ng/mL: Gray zone; about 25% of these men may have cancer.

>10 ng/mL: Higher suspicion; about 50% or more could have cancer.

2. PSA Velocity (Change Over Time)

An increase of more than 0.75 ng/mL per year may indicate higher risk.

3. PSA Doubling Time

A doubling of PSA within 3 years can suggest a more aggressive cancer.

4. Free vs. Total PSA

Lower free PSA (<10%) increases cancer risk.

5. PSA Density

Adjusts PSA level by prostate volume (from imaging). High PSA density may indicate cancer in larger prostates.

Here’s a simplified visual of two different PSA trends over time:

Year | Case A: Benign | Case B: Cancer

---------|----------------|----------------

2020 | 2.5 | 3.2

2021 | 2.7 | 4.1

2022 | 2.8 | 6.0

2023 | 3.0 | 9.8

2024 | 3.1 | 14.5- Case A: Slow rise suggests benign condition.

- Case B: Rapid increase suggests aggressive cancer.

Doctors consider the overall trend, rate of change, and other individual risk factors when deciding on further tests or biopsies.

The Spectrum of Prostate Cancer Types

Not all prostate cancers behave the same. Some are slow-growing and may never pose a significant health risk, while others are aggressive and can spread quickly.

1. Adenocarcinoma (Acinar Type): This is the most common type, accounting for over 90% of cases. It typically arises in the glandular cells of the prostate. Within this category, there is a wide range of aggressiveness, often graded by the Gleason score.

2. Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A rarer and often more aggressive variant, ductal adenocarcinoma tends to grow and spread faster than acinar prostate cancer and may present with urinary symptoms earlier.

3. Small Cell Carcinoma and Other Neuroendocrine Tumors: These are highly aggressive and rare. Small cell carcinoma, for instance, doesn’t usually produce PSA, making it particularly difficult to detect through standard screening. These cancers often metastasize early and require a different treatment approach.

4. Sarcomas and Transitional Cell Carcinoma: These very rare forms originate from the prostate’s structural or transitional tissues. Their prognosis tends to be poor, largely because they are typically diagnosed at a late stage.

Stage IV at Diagnosis: A Troubling Reality

For a notable percentage of men, prostate cancer is not found until it has already spread—commonly to the bones, lymph nodes, liver, or lungs. By the time of Stage IV diagnosis, treatment typically shifts from curative to palliative, aiming to slow progression and manage symptoms.

One high-profile case is that of actor Dennis Hopper, who revealed his prostate cancer diagnosis in 2009. By the time of public disclosure, his cancer had already metastasized. Despite aggressive treatment, he died less than a year later. His story illustrates the disease’s stealth and speed.

Another lesser-known but striking case involved Australian tennis coach Peter Carter, best known for mentoring Roger Federer. Diagnosed very late due to subtle symptoms and misinterpretation of PSA levels, he passed away from advanced prostate cancer at a relatively young age.

These cases highlight the difficulties of early recognition and the devastating consequences of late-stage diagnosis.

Diagnostic Tools: Improving but Imperfect

While PSA remains the frontline screening method, newer tools are gradually enhancing our ability to detect prostate cancer early:

- MRI (Multiparametric MRI): Offers a more detailed view of the prostate, helping identify suspicious areas that warrant biopsy.

- Biopsies (Traditional and Fusion-guided): Targeted biopsies guided by MRI images can improve detection accuracy, especially for aggressive cancers.

- Genomic Testing: Some tests analyze gene expression in prostate cells to assess cancer risk or aggressiveness, aiding treatment decisions.

Yet, no single test offers perfect accuracy. Doctors often need to consider PSA trends over time, imaging results, and clinical judgment together.

Balancing Screening and Overdiagnosis

While aggressive cancers are a serious threat, many prostate cancers grow so slowly that they pose minimal risk over a man’s lifetime. This creates a diagnostic dilemma: how to distinguish between cancers that need treatment and those that don’t.

Overdiagnosis can lead to overtreatment, with potential side effects like incontinence and erectile dysfunction. As a result, some men with low-risk prostate cancer opt for active surveillance—closely monitoring the cancer rather than treating it immediately.

What Can Be Done?

Awareness is key. Men, particularly those over 50 or with a family history of prostate cancer, should discuss screening options with their doctors. African American men and those with BRCA mutations may face a higher risk and may benefit from earlier or more frequent screening.

Encouraging open conversations about urinary health and screening, even when symptoms seem minor or absent, can lead to earlier detection. The more we understand about the biology and behavior of different prostate cancers, the better we can tailor both diagnosis and treatment.

In Summary

Prostate cancer is a complex disease with a wide spectrum of presentations. Its ability to grow silently, combined with the limitations of current screening tools, contributes to many men receiving a diagnosis only after the disease has spread. Yet, through a combination of informed screening, evolving diagnostics, and public awareness, we can improve outcomes and reduce the number of late-stage diagnoses.

If you or a loved one is navigating prostate cancer, remember: information is power, and you’re not alone.

Disclaimer: This blog post is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance