Imagine you’re cheering on your immune system, giving it the best “training camp” so it can fight cancer cells as fiercely as possible. That’s basically what therapeutic cancer vaccines do. Instead of preventing disease, like a flu shot, these vaccines are designed to tackle a cancer you already have. They “teach” your immune cells to recognize and destroy tumor cells that slipped under the radar before. It’s a groundbreaking field full of hopeful promise, especially now that technologies like mRNA vaccines have shown the world just how powerful they can be.

Before we dive into the different experimental vaccines, let’s talk about realistic expectations. While there’s a lot of excitement (and with good reason), most of these vaccines are still in relatively early testing. That means they’re not yet available as routine treatments. But each year, we learn more about which vaccines work best, for which types of cancers, and in which scenarios. Ultimately, scientists hope these shots will help patients live longer, fend off recurrences, and experience fewer side effects compared to heavier-duty treatments alone.

Now, let’s explore some of the therapeutic cancer vaccines in human clinical trials. Some are already moving into larger studies because their early data looked promising—where cancer responded well or stayed in remission longer than usual. Others are just starting Phase 1 trials, but even that is a big step forward, because it takes real scientific merit to get this far. We’ll look at mRNA vaccines, peptide vaccines, dendritic cell vaccines, and more, all from different parts of the globe, although we’re focusing on the U.S., Europe, Japan, and China for this roundup.

Overview of investigational therapeutic cancer vaccines

Moderna’s Personalized mRNA Vaccine (mRNA-4157 or V940) is one name you may have heard in the news. It’s tested against melanoma—specifically, advanced melanoma where doctors worry the tumor might come back after surgery. In early clinical trials, patients who got the vaccine plus the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab did significantly better than those who only got pembrolizumab. The vaccine is individually tailored for each patient’s cancer, which means doctors examine your tumor’s unique genetic makeup, then design a vaccine that attacks those specific mutations. This personalized approach is incredibly encouraging because it targets what’s unique about your cancer, while aiming to leave healthy cells alone.

Another mRNA vaccine option also focusing on melanoma is BNT111 from a German company called BioNTech. Instead of being custom-built for each patient, this one is an “off-the-shelf” formula that targets four antigens often found in melanoma cells. Think of it like a multi-purpose key designed to open the lock in many melanoma tumors. Results from its Phase 2 trial showed that, combined with a commonly used immunotherapy, it could spark meaningful immune reactions and shrink tumors in people who had run out of other options.

In the realm of personalized vaccines, BioNTech and Genentech have teamed up to develop Autogene Cevumeran (also known as BNT122). This one is being tested in pancreatic cancer, which has historically been incredibly hard to treat. Early findings suggest that some patients’ immune systems can be trained to fight off leftover cancer cells after surgery. Patients who got the vaccine in a small trial were less likely to relapse. That’s a big deal for a type of cancer that often comes roaring back.

Speaking of hard-to-treat cancers, glioblastoma—a serious brain tumor—has been the focus of two vaccine contenders: DCVax-L from Northwest Biotherapeutics and SurVaxM from MimiVax. While neither vaccine has received full approval yet, early studies suggest some patients with glioblastoma are living longer than we’d typically expect. For families battling this tough disease, even a few more months or years can feel like a major victory.

There’s also a “universal” approach with UV1 from Ultimovacs, a Norwegian company, which is in multi-country trials. It targets an enzyme called telomerase that most cancer cells need to keep growing. By training your immune system to spot and attack cells producing too much telomerase, UV1 could, in theory, help patients with many different tumor types.

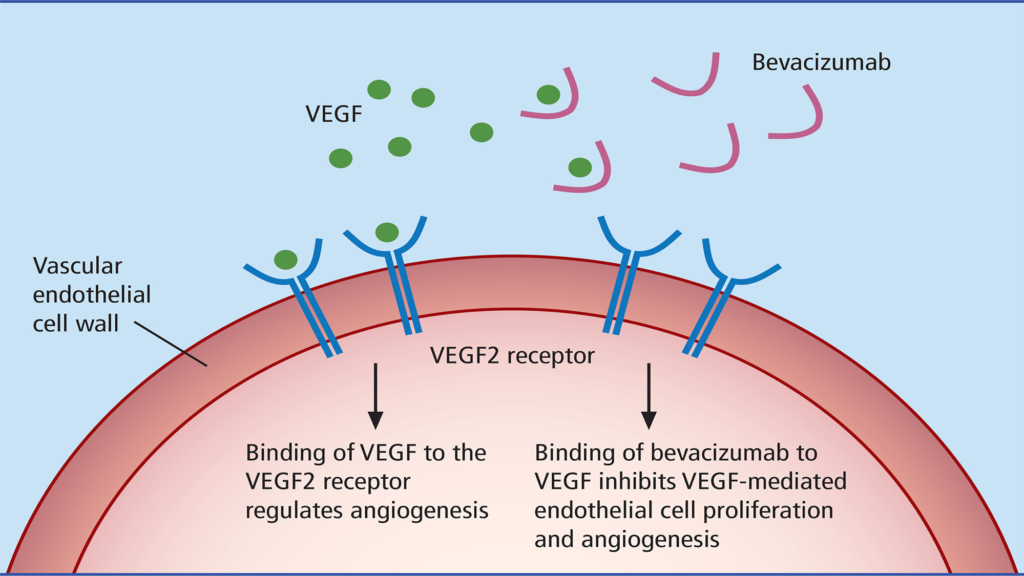

Some vaccines take a more direct aim at the immune-dampening signals cancers rely on. For example, IO Biotech’s IO102-IO103 tries to undo the tumor’s “invisibility cloak” by blocking molecules like PD-L1 and IDO, which tumors use to hide from immune cells. Early data in advanced melanoma are intriguing, and larger trials are now underway.

Certain vaccines, like Imugene’s HER-Vaxx, go after specific proteins, such as HER2, that drive cancer growth. In the case of HER-Vaxx, this protein is found in some stomach cancers (and also in breast cancers). A recent Phase 2 trial showed that patients who got this vaccine plus chemotherapy lived longer than those who just got the chemo. That’s the kind of hopeful news we need more of when it comes to stomach and esophageal cancers.

KRAS is another cancer-driving culprit that was once considered “undruggable.” But ELI-002 from Elicio is bravely targeting KRAS mutations common in pancreatic and some other solid tumors. Scientists are testing ELI-002 after patients undergo surgery for early-stage cancer, aiming to prevent the disease from coming back. Results so far have been encouraging enough to push into bigger trials.

China is also stepping up in the personalized vaccine arena with LK101 from Likang, which uses mRNA to program a patient’s own immune cells to attack their tumor. Though it’s still early-stage, it’s a meaningful marker of global progress, as more countries invest in high-tech solutions to cancer.

Conclusion and outlook

So, what does all this mean for patients and caregivers? First, it’s okay to feel excited. We’re finally seeing real clinical benefits from cancer vaccines, and those benefits will likely grow as research continues. But these treatments aren’t yet commonplace. Most of these vaccines are only available through clinical trials, and it can take years for them to complete the necessary testing and be approved. The silver lining is that for many patients, especially those who have exhausted other treatment options, enrolling in these trials could offer new hope, while also contributing to crucial scientific advances.

If you or your loved one is exploring new therapies and wants to consider a clinical trial, it’s always best to talk it through with a doctor who knows your specific situation. Not every vaccine is right for every cancer patient, but the fact that there are so many different vaccines in the pipeline means more potential matches for different cancers. Ultimately, the real promise here is that vaccines might one day stop cancers from returning, or at least reduce how aggressive they become. And that possibility—of turning cancer into something more manageable and less terrifying—is a beacon of hope for so many families worldwide.

If you want to learn more about these clinical trials or see if you might qualify, you can often look them up on platforms like ClinicalTrials.gov, or get referrals from oncologists who participate in research. While we’re in the early chapters of this story, the momentum is undeniable. The prospect of harnessing your body’s own immune system to keep cancer at bay feels like a breakthrough long in the making. And right now, we’re closer to it than ever before.

Source: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Merck, American Brain Tumor Association, GlobeNewswire, Biospace.