Metastatic breast cancer (mBC) is breast cancer that has spread beyond the breast to other parts of the body, such as bones, liver, lungs, or brain. While treatable, mBC is considered stage IV cancer and is not currently curable. Patients often undergo multiple lines of therapy to keep the disease under control. Over time, cancers can become resistant to treatments, creating a pressing need for new options. Fortunately, research is bringing forward promising new therapies. This article will explore five emerging treatments as of 2025 – capivasertib + Faslodex (fulvestrant), trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu), camizestrant + Verzenio (abemaciclib), inavolisib (GDC-0077) + fulvestrant, and EDP-202 (eftilagimod alpha) – and how they address current unmet needs in mBC. We’ll look at each therapy’s purpose, how it can help patients, approval status, effectiveness, side effects, comparisons to standard treatments, and even share some real patient stories from clinical trials. The goal is to provide you, patients and caregivers, with an in-depth, yet accessible and hopeful overview of advances on the horizon.

Unmet Needs in Metastatic Breast Cancer

Even with many treatments available for metastatic breast cancer, there are significant unmet needs that researchers are striving to address:

- Overcoming Hormone Therapy Resistance: About 70% of breast cancers are hormone receptor-positive (HR+), meaning they grow in response to hormones like estrogen. Treatments like aromatase inhibitors and anti-estrogen drugs can slow these cancers, but eventually many tumors become resistant. Patients whose cancer progresses despite these therapies need new options to control disease.

- Treating HER2-Low Breast Cancer: Approximately 15-20% of breast cancers are HER2-positive, meaning they overproduce the HER2 protein and can be targeted by drugs like Herceptin. But there’s also a group called HER2-low – tumors that have some HER2 but not enough to be “HER2-positive.” Historically, HER2-low patients were treated like HER2-negative patients, without HER2-targeted drugs. This left a gap in therapy options for many people.

- Targeting Genetic Alterations: Some metastatic breast cancers have specific genetic alterations that help drive the cancer, such as mutations in the PIK3CA gene (part of the PI3K pathway) or loss of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene. There are a few targeted drugs for these (for example, alpelisib / Piqray for PIK3CA mutations), but side effects can be difficult and not all patients benefit. New targeted therapies that can work better or with fewer side effects are needed.

- Making Treatments More Manageable: Standard treatments like chemotherapy can cause significant side effects and impact quality of life. There is a need for therapies that extend life while preserving quality of life, whether by being more targeted (to spare healthy cells) or by being easier to administer (like pills instead of IV infusions or injections).

- Engaging the Immune System: Immunotherapy (which helps the body’s own immune system fight cancer) has transformed treatment in some cancers (like melanoma and lung cancer). But in breast cancer, immunotherapy success has mostly been limited to triple-negative cases with certain markers. Most breast cancers (especially HR+ tumors) haven’t responded well to current immunotherapies. Finding a way to spur the immune system against breast cancer could open a new front in treatment.

Each of the new therapies discussed below aims to tackle one or more of these unmet needs. It’s an exciting time in research, and many oncologists are now saying that metastatic breast cancer is becoming more of a “chronic disease” that can be managed long-term, even if not cured. As Dr. Joanne Mortimer, a breast oncologist, noted about her patient Sabrina: “many new therapies are coming,” and indeed Sabrina’s cancer has been kept “shrunk and stable” for nearly five years with successive treatments. Let’s dive into the specifics of these breakthroughs.

Capivasertib + Fulvestrant: Tackling Resistance via the AKT Pathway

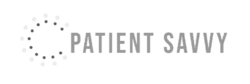

One major challenge in HR-positive metastatic breast cancer is resistance to hormone therapy. Capivasertib is a new targeted drug designed to address this by inhibiting AKT, a key protein in the PI3K/AKT pathway that cancer cells often exploit to grow and resist treatment. Capivasertib is given as a pill. It’s used in combination with fulvestrant (Faslodex), an injected hormonal therapy that degrades estrogen receptors. Fulvestrant alone is a standard treatment once the cancer progresses on initial hormone therapies, but adding capivasertib offers a powerful one-two punch: fulvestrant cuts off the tumor’s estrogen fuel, while capivasertib shuts down an alternate growth route (the AKT pathway) that cancer cells commonly activate when they become resistant to endocrine therapy

How does this new combo help?

In a phase III trial called CAPItello-291, adding capivasertib significantly delayed cancer progression. Among all patients in the trial (regardless of specific mutations), the median progression-free survival (time during which the cancer did not grow) was 7.2 months with capivasertib + fulvestrant vs. 3.6 months with fulvestrant alone. In other words, patients on the new drug combo had about double the time before their cancer worsened. Importantly, the benefit was even greater in patients whose tumors had mutations in the PI3K/AKT pathway (such as PIK3CA, AKT1, or PTEN alterations). In that subgroup, median progression-free survival was 7.3 months vs. only 3.1 months on fulvestrant alone. This indicates capivasertib is particularly effective for those mutation-driven cancers. Many patients in the trial had already received prior treatments like CDK4/6 inhibitors (e.g., Ibrance, Kisqali, or Verzenio), so showing improvement in this tough setting is a big step forward.

Approval status:

Based on these results, capivasertib (brand name Truqap in some regions) was approved by the U.S. FDA in November 2023. The approval is for HR-positive, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer with one of those PI3K/AKT pathway mutations, in patients whose cancer has progressed on at least one prior endocrine therapy. In April 2024, European regulators also gave a positive opinion, and the drug combination is now approved in the EU as well. What this means for patients is that, if your tumor has a qualifying mutation (detected via a special lab test), and your cancer got worse after treatments like aromatase inhibitors (with or without a CDK4/6 inhibitor), you have a new option beyond just fulvestrant alone.

Expected efficacy:

Patients should understand that this treatment isn’t a cure, but it slows down the cancer significantly. By roughly doubling the time to progression, it can give patients months of extra disease control. It’s not uncommon now for oncologists to layer these new drugs one after the other, potentially keeping the cancer at bay for years. As one patient advocate observed, “even outdated statistics may not apply to today’s treatment landscape” because newer drugs keep pushing survival further. Every extra chapter we can add to a patient’s story is meaningful.

Side effects:

In the trial, the combination was generally well tolerated. The most common side effects were diarrhea and skin rash. These happened because AKT is involved in normal cell signaling in the gut and skin, but most cases were manageable with medications (like anti-diarrheal pills or creams for rash) and dose adjustments. A smaller number of patients experienced high blood sugar (hyperglycemia), since the AKT pathway also affects insulin signaling. For that reason, doctors will monitor blood sugar levels – especially in patients who are diabetic – during treatment. Importantly, serious side effects were relatively infrequent. In the trial, only about 13% of patients on capivasertib had to stop treatment due to side effects, compared to 2% on placebo. This means about 87% of patients were able to stay on the drug, indicating that for most, the side effects were not unbearable. Doctors have become experienced in managing similar side effects from older drugs like alpelisib (a PI3K inhibitor), so they have strategies to keep patients feeling as good as possible.

Comparison to existing standard of care:

The current standard for someone in this situation (HR+ cancer progressing after initial hormonal treatments) might include fulvestrant alone, or fulvestrant plus another targeted drug if appropriate. One existing targeted drug is alpelisib (Piqray), which targets a related part of the pathway (PI3K) for patients with PIK3CA mutations. However, alpelisib is typically used after CDK4/6 inhibitors, and it can cause substantial blood sugar issues, limiting some patients from using it. Capivasertib provides a new alternative, one that appears effective even if there’s no PIK3CA mutation (though the benefit is largest when a mutation is present)

It also attacks the pathway at a different point (AKT), which might overcome resistance that develops to PI3K inhibitors. In practice, if a patient’s tumor has the mutation and qualifies, an oncologist may favor starting capivasertib+fulvestrant now that it’s available, potentially even instead of alpelisib in some cases. Clinical judgment will depend on the patient’s prior therapies and health factors (for example, a diabetic patient might actually handle capivasertib better than alpelisib due to lower hyperglycemia risk). For patients without a pathway mutation, capivasertib isn’t formally approved, but interestingly even those patients saw some benefit in trials (just smaller). Research is ongoing to see if capivasertib could help a broader group or be combined with other agents.

Patient perspective:

For patients like Linda, who saw her cancer grow after an initial two years on hormonal therapy + a CDK4/6 inhibitor, the approval of capivasertib meant a new lease on controlling the disease. Instead of moving straight to IV chemotherapy (which comes with hair loss, fatigue, etc.), she was able to start a pill in a clinical trial. Her scans showed that her tumors stopped growing, and some even shrank. “It was a relief,” she recalls, “to have something that worked when the usual treatments stopped working.” Now that the drug is approved, many more patients will have the chance to extend their time on effective, relatively tolerable therapy before chemotherapy is needed. Oncologists emphasize that each additional month without cancer progression is time patients can spend living life – attending a child’s graduation or taking that vacation – not just cycling through hospital visits. As one researcher said about the approval, it is “welcome news” and it’s important to test patients’ tumors for these biomarkers to identify who can benefit.

Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (Enhertu): A Game-Changer for HER2+ and HER2-Low Disease

For patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, treatments that target the HER2 protein have dramatically improved outcomes over the past two decades. Drugs like trastuzumab (Herceptin) and T-DM1 (Kadcyla) were game-changers. However, most HER2+ metastatic patients eventually see their cancer progress after those treatments, and they need new options. Moreover, until recently, if a tumor was “HER2-low” (having some HER2 expression but not enough to qualify as HER2+), there was no targeted therapy for HER2 – those patients were treated with endocrine therapy if HR+, or chemotherapy if triple-negative.

Trastuzumab deruxtecan, known by the brand name Enhertu, is a new type of drug called an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC). It’s sometimes abbreviated T-DXd. Essentially, it’s like a smart bomb against cancer cells: a molecule of trastuzumab (an antibody that finds HER2) linked to a potent chemotherapy drug (deruxtecan) that it delivers directly to the HER2-expressing cell. Enhertu can attach to even low levels of HER2 on cancer cells. Once attached, the whole complex is taken into the cell and the chemo payload is released inside, where it can kill the cancer cell from within. An added bonus is something called the “bystander effect” – the released chemo drug can diffuse and kill neighboring cancer cells that might not have HER2, as long as they are near a HER2-positive cell. This is useful in tumors that are a mix of HER2-positive and HER2-negative cells, or those HER2-low tumors where not every cell has the target.

How it helps:

Enhertu has shown remarkable efficacy in clinical trials for both HER2-positive and HER2-low metastatic breast cancer. In HER2-positive patients who had already received prior treatments (like Herceptin and Kadcyla), Enhertu not only shrank tumors in a majority of patients, it kept the cancer at bay far longer than the previous standard. In a head-to-head phase III trial (DESTINY-Breast03), Enhertu was compared to T-DM1 (Kadcyla) in patients whose HER2+ cancer had progressed after initial therapy. The results were striking: 12 months after starting treatment, about 76% of patients on Enhertu were alive without their cancer progressing, compared to only 34% of those on T-DM1. This was a dramatic improvement – more than doubling the proportion of patients with their disease under control at one year. In fact, the Enhertu was so much better that the trial was stopped early to allow the T-DM1 patients to switch to Enhertu. These findings have made Enhertu the preferred second-line therapy for HER2-positive mBC now.

Perhaps even more groundbreaking was the DESTINY-Breast04 trial, which looked at Enhertu in HER2-low metastatic breast cancer (most of these patients were HR-positive as well). Before Enhertu, HER2-low patients would typically just continue on hormone therapy or switch to chemotherapy because HER2-targeted drugs weren’t thought to work for them. DESTINY-Breast04 showed that in HER2-low patients, Enhertu nearly doubled the progression-free survival compared to standard chemotherapy. The median time without cancer growth was significantly longer, and importantly, this translated into these patients living longer overall as well. This was the first time a targeted drug showed clear benefit in HER2-low breast cancer, essentially creating a new treatment category.

Approval status:

Enhertu was first approved in late 2019 for HER2-positive breast cancer after two or more prior anti-HER2 therapies (based on an earlier trial called DESTINY-Breast01). By 2022, with the DESTINY-Breast03 results, the FDA expanded approval to include HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer after just one prior HER2 treatment

This means if a patient had HER2+ cancer and it spread or came back after initial treatment (e.g., after Herceptin + chemo), Enhertu could be used next. In August 2022, following DESTINY-Breast04, the FDA also approved Enhertu for HER2-low metastatic breast cancer. Specifically, this approval is for patients who have received at least one prior line of chemotherapy for metastatic disease (if HR-positive, they should also have received hormone therapy). The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has similarly approved Enhertu for these indications. In short, for HER2 3+ tumors or HER2-low (defined as HER2 1+ or 2+ by tests) tumors, Enhertu has become part of the treatment arsenal.

Expected efficacy:

For HER2-positive patients, Enhertu has been shown to shrink tumors in the majority of patients – even when prior HER2 therapies stopped working. Many patients experience a meaningful period of disease remission or stability. Some patients have responses lasting a year or more. In HER2-low patients, the benefit is also significant, giving on average several additional months of control compared to chemo, and improving survival. It’s important to remember that individual results vary: some tumors respond extremely well, others may eventually find a way around the drug. But overall, these outcomes have given patients more time – time that can be used to enjoy life, make memories, or pursue further treatments down the line. One metastatic breast cancer thriver, Tiffany, shared that she was one of the first patients at her cancer center to receive Enhertu in 2019, and that ongoing research (and access to drugs like Enhertu) has kept her alive and able to be with her young children since her stage IV diagnosis in 2018. She notes that thanks to these new treatments, “at this point, for a lot of us, it’s like treating a chronic disease.” Patients are living longer with metastatic breast cancer than before – truly a testament to research progress.

Side effects:

Because Enhertu delivers a potent chemotherapy, it does come with side effects, though the targeted delivery aims to reduce how much of the chemo affects healthy cells. Common side effects include nausea, fatigue, hair loss, low white blood cell counts, and anemia, similar to traditional chemo. These are usually manageable with standard supportive care (anti-nausea medication, growth factors for blood counts, etc.). One unique serious side effect with Enhertu is the risk of interstitial lung disease (ILD), which is an inflammation of the lungs

In clinical studies, about 10-15% of patients on Enhertu experienced some lung inflammation; most cases were mild or moderate and got better with prompt steroid treatment and stopping the drug. However, a few cases were severe – tragically, in an early trial, about 5 out of 184 patients (roughly 2.7%) died due to ILD. This has made doctors very vigilant: patients on Enhertu are closely monitored for symptoms like cough or shortness of breath. If a patient develops any lung symptoms, the care team will typically pause treatment, do scans, and start corticosteroids if ILD is suspected. By catching it early, the vast majority of ILD cases can be reversed. This risk underscores the balance of being hopeful but realistic – Enhertu can work wonders against the cancer, but patients and providers must be mindful of and manage the risks. Aside from ILD, other side effects like fatigue can accumulate over time, so quality-of-life monitoring is important. Dose adjustments can be made if needed to strike a balance between efficacy and tolerability.

Comparison to standard of care:

For HER2-positive disease, Enhertu has effectively replaced T-DM1 (Kadcyla) as the second-line standard-of-care after initial therapy. First-line treatment for HER2+ mBC is still usually a combination of antibodies trastuzumab (Herceptin) + pertuzumab (Perjeta) with chemotherapy. But if the cancer grows after that, many oncologists will now reach for Enhertu next, given the superb results compared to the older standard Kadcyla. For HER2-low patients, there was no standard targeted therapy before – it was an unmet need. Enhertu filled that void, and for a patient who qualifies as HER2-low and has already tried at least one chemo, Enhertu would likely be offered, because it’s proven to extend survival relative to continuing standard chemo. In essence, Enhertu has expanded the reach of HER2-targeted therapy to a wider population of patients and moved up to an earlier role in treatment sequencing. Researchers are even testing Enhertu in earlier-stage breast cancer and other cancers that have HER2, because of how effective it is.

Real-life patient stories:

The impact of Enhertu is perhaps best illustrated by patient experiences. Sabrina, a 37-year-old with HER2-positive mBC, had exhausted several treatments and even became wheelchair-bound due to cancer in her spine. After transferring her care, her doctors put her on Enhertu. The results were remarkable – her scans showed her cancer shrunk, and her debilitating pain diminished. Over time, Sabrina went from being in a wheelchair to walking and living an active life: exercising, gardening, and even babysitting for her church community. Knowing the disease could not be cured, she instead focused on living with quality. Five years after her metastatic diagnosis, Sabrina’s cancer remains under control with treatment, and she shares her story to encourage others, saying “I’m not looking for longevity, but quality of life… I live with it. It’s part of me, but not the whole me. Enjoy the moment!”. Another patient, Tiffany (mentioned above), also benefited from Enhertu after her HER2-positive cancer spread to her lungs, bones, and liver. She too has had several years of time with her young children that she attributes to being able to go on “all these new treatments” that weren’t available a decade ago. Even patients with HER2-low cancer have new hope. Advocate Janice Cowden attended a medical conference in 2022 and was moved to tears hearing the DESTINY-Breast04 results that led to Enhertu’s approval for HER2-low disease. “I had tears, I had goosebumps,” she said, describing the moment when thousands of doctors and researchers gave a standing ovation to the trial findings. For Janice, who lives with metastatic breast cancer herself, that data meant that countless patients like her would get more time and a chance at a better life. These stories underline a theme: progress is being made, and patients are directly seeing the benefits.

Camizestrant + Verzenio: Next-Generation Hormonal Therapy for Resistant HR+ Cancer

When it comes to HR-positive metastatic breast cancer, blocking estrogen is a cornerstone of treatment. However, tumors often develop clever ways to grow even when standard hormone therapies are used. One common trick is a mutation in the estrogen receptor gene (ESR1 mutation), which can make the receptor active even without estrogen, or alter its shape so that drugs like aromatase inhibitors (which lower estrogen levels) are less effective. In such cases, the cancer becomes less responsive to standard endocrine therapy. Camizestrant is a promising experimental drug in a class called oral SERDs (Selective Estrogen Receptor Degraders). SERDs not only block the estrogen receptor, they also mark it for destruction. Fulvestrant (Faslodex) is a SERD too, but it’s an injection given in the muscle and has limited ability to eliminate all estrogen receptors (partly due to dose limitations of an injection). Camizestrant, by contrast, is a pill that can be taken orally, and early research shows it may degrade the estrogen receptor more completely, including mutant receptors, and thus overcome resistance

In practice, camizestrant is being studied both alone and in combination with other therapies. The combo we highlight here is camizestrant + abemaciclib (Verzenio). Abemaciclib is a CDK4/6 inhibitor, a type of targeted pill that has become standard with initial endocrine therapy for HR+ metastatic breast cancer. CDK4/6 inhibitors (palbociclib/Ibrance, ribociclib/Kisqali, or abemaciclib/Verzenio) help stop cancer cell division and have significantly extended survival for patients when added to hormone therapy in the first-line setting. The idea of combining camizestrant with a CDK4/6 inhibitor is to create a powerful first-line treatment or a treatment for ESR1-mutant cancers that can delay resistance even further.

How it helps:

Camizestrant has shown very encouraging results in clinical trials. In the SERENA-2 trial (phase II), camizestrant was compared head-to-head against fulvestrant in patients with advanced HR+ breast cancer who had prior endocrine therapy. Camizestrant significantly improved progression-free survival over fulvestrant. Notably, in the subgroup of patients whose tumors had ESR1 mutations (about 40% of the trial group), camizestrant worked especially well – these patients had an even greater reduction in the risk of progression compared to fulvestrant. In patients without ESR1 mutations, the benefit was more modest (meaning standard therapies still work okay if no mutation). This confirms that drugs like camizestrant are particularly valuable for overcoming that specific resistance mechanism.

Building on these results, a larger phase III trial called SERENA-6 is examining camizestrant plus a CDK4/6 inhibitor (like abemaciclib) versus the current standard (an aromatase inhibitor plus CDK4/6 inhibitor) in the first-line setting for patients who develop an ESR1 mutation. Early topline data from SERENA-6 (announced in late 2024) indicates that switching to camizestrant + CDK4/6 when an ESR1 mutation is detected significantly prolongs progression-free survival compared to continuing the standard therapy. In simpler terms, if a patient is on first-line therapy and blood tests show their tumor has acquired an ESR1 mutation (a sign of emerging resistance), moving them to camizestrant may keep the cancer controlled longer than staying on the original treatment. This adaptive strategy could become a new paradigm – treating based on real-time molecular changes in the cancer.

It’s important to note that as of early 2025, camizestrant is still investigational – it’s not yet approved for general use. But AstraZeneca (the company developing it) has reported positive results and is likely to seek approval. Doctors and patients may access it through clinical trials. The combination of camizestrant + Verzenio (or other CDK4/6 inhibitors) could become a new standard if ongoing trials confirm the benefits. The vision is that by using a more potent estrogen blocker (camizestrant) alongside cell-cycle blockade (CDK4/6 inhibitor), we can delay the need for chemotherapy even further, keeping patients on oral therapies with manageable side effects for longer.

Side effects:

What can patients expect if they go on camizestrant (likely in a trial at this point)? The good news is that camizestrant is generally well tolerated. In trials, the most common side effects have been mild nausea and vomiting, similar to what some people experience with hormonal therapies or the CDK4/6 pills. These can often be managed by taking the medication with food or using anti-nausea tablets if needed. There are a couple of unique side effects that have been observed with camizestrant and some other oral SERDs, but they sound scarier than they usually are: some patients reported visual disturbances called phosphenes – basically seeing brief flashes of light or “trailing” lights in their vision. This is a known on-target effect of SERDs (meaning it’s related to how the drug works, possibly affecting receptors in the eye). In trials, these visual side effects were mostly Grade 1 (very mild) and tended to occur at higher doses; at the dose likely to be used (75 mg), they were much less common. They are reversible (go away when the drug is stopped or even as the body adjusts over time). Another effect was asymptomatic bradycardia, which means a slower than normal heartbeat without any symptoms. Again, this was rare and dose-dependent. Patients didn’t feel anything from it, but it showed up on EKGs. Doctors will monitor heart rate and EKG periodically if you’re on this medication, but the low dose chosen for phase III had minimal impact on heart rate

Aside from these, the combination of camizestrant + a CDK4/6 inhibitor will also carry the typical side effects of CDK4/6 inhibitors: mainly lowered blood counts (especially white cells), potential fatigue, and sometimes diarrhea (which is most common with abemaciclib/Verzenio). Most patients on CDK4/6 inhibitors find the first couple of months the most challenging as the body adapts, and then side effects often become quite manageable. There is frequent blood test monitoring to ensure counts aren’t too low. Overall, camizestrant’s side effect profile is considered manageable and “reasonably well tolerated”. The absence of any need for intravenous infusions is a big plus for quality of life – these are pills you take at home.

Comparison to existing treatments:

Currently, if a patient’s HR+ metastatic breast cancer progresses after initial therapies, options include fulvestrant injections (with or without targeted drugs like capivasertib or alpelisib if appropriate), or newer oral SERDs like elacestrant (Orserdu) which was approved in early 2023 for post-menopausal women with ESR1-mutated metastatic breast cancer after at least one line of endocrine therapy. Elacestrant was actually the first oral SERD to get approved, based on the EMERALD trial, and it showed a modest but real benefit for ESR1 mutant cancers. Camizestrant is part of this same wave of next-generation SERDs, but it might prove to be even more effective based on the trial data so far (though it’s not a head-to-head comparison with elacestrant). If camizestrant gets approved, doctors will have to decide which SERD to use – it’s encouraging to have multiple choices. According to experts, multiple oral SERDs “with distinct toxicity profiles” are coming, and figuring out the optimal sequencing (which to use when) and which patients benefit the most (for example, based on specific ESR1 mutations) will be key.

One can imagine a future where a patient might start on an AI + CDK4/6; if an ESR1 mutation arises, switch to camizestrant + CDK4/6; if it progresses further, maybe try elacestrant or fulvestrant, etc., before moving to chemo. It’s all about extending the time on effective, less intensive therapy. Compared to fulvestrant, camizestrant’s obvious advantage is convenience (pill vs injection) and possibly better tumor control (since it can achieve higher effective doses). Compared to aromatase inhibitors, camizestrant might be used after AI resistance or potentially in place of an AI in some settings if data supports. We will also likely see camizestrant tested in the adjuvant setting (after surgery in early breast cancer) to see if it can reduce recurrence better than current endocrine therapy for high-risk cases – but that’s in the future.

Patient perspective:

While we don’t have published patient stories on camizestrant yet (as it’s new and in trials), we can imagine how this kind of advancement might feel. Consider a patient, Maria, who has been on the standard first-line treatment (letrozole + palbociclib) for two years. It worked well until recent scans showed a new liver spot. Her blood test reveals an ESR1 mutation, explaining why the cancer is escaping the aromatase inhibitor. Instead of going to chemotherapy, Maria is offered a trial of camizestrant + abemaciclib. After a month on the trial, her liver lesion starts shrinking. She experiences a bit of nausea and some fatigue, but she’s relieved to avoid IV chemo. She can continue her job and daily routine with minimal interruption. In her words, “It’s a pill I take each day, and it’s keeping my cancer in check. I had a few episodes of seeing tiny sparkles in my vision, which was weird but not painful – the doctor said it’s a known quirk of the drug. Small price to pay for more time without progression.” This hypothetical scenario mirrors what trial investigators have noted: patients appreciate oral drugs that allow them to maintain normalcy. Dr. Erica Mayer, an oncologist involved in SERENA-2, remarked that the efficacy and safety seen “support further camizestrant development”. Experts are optimistic that having more of these oral hormone fighters will improve patient outcomes and comfort, giving doctors better tools to personalize therapy

Inavolisib (GDC-0077) + Fulvestrant (and Palbociclib): Targeting PI3K Mutations for Better Outcomes

In the realm of precision medicine, another exciting development is inavolisib, previously known as GDC-0077. This drug targets the PI3K pathway, specifically PI3K-alpha, and is designed primarily for cancers with PIK3CA mutations. PIK3CA mutations occur in roughly 30-40% of HR+ breast cancers and can make the cancer more aggressive and resistant to hormone therapy. We already have one PI3K inhibitor approved – alpelisib (Piqray) – which, when combined with fulvestrant, has been a standard for PIK3CA-mutant cancers after initial therapies. However, alpelisib has notable side effects and not all patients can tolerate it. Inavolisib is a next-generation PI3K inhibitor that researchers hope may be more effective or easier to combine with other treatments. One strategy being tested is adding inavolisib up front, in the first-line setting, alongside the now-standard duo of an endocrine therapy plus a CDK4/6 inhibitor.

How it helps:

The phase III trial INAVO-120 evaluated inavolisib in a three-drug combination: inavolisib + palbociclib (Ibrance) + fulvestrant, compared to the control of palbociclib + fulvestrant without inavolisib, in patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer who have PIK3CA mutations. These patients had not received prior therapy for metastatic disease (or had a recurrence soon after adjuvant therapy), making this a first-line treatment for them. The results were very promising: the addition of inavolisib reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 57% compared to the standard regimen. Numerically, the median progression-free survival was 15.0 months with inavolisib versus 7.3 months without it. This doubling of PFS is a huge win, especially considering palbociclib + fulvestrant is already an effective combo. Essentially, in patients with that mutation, giving a PI3K inhibitor right away (instead of waiting until later lines) kept the cancer controlled for significantly longer.

To put that into perspective, typically an HR+ metastatic patient might get ~1.5 to 2 years on first-line AI + CDK4/6, then if they have a PIK3CA mutation, ~5-7 months on fulvestrant + alpelisib in second-line (based on trials), etc. Here we’re seeing the possibility of extending the first-line to well beyond a year by intensifying treatment for those with a known mutation. The hope is that by hitting the cancer hard at the outset (blocking estrogen receptors, blocking CDK4/6, and blocking PI3K signaling all at once), we can delay resistance from emerging.

Approval status:

Seeing the strong results, Genentech (the developer) has submitted inavolisib to the FDA. In May 2024, the FDA granted Priority Review to the new drug application for inavolisib in combination with palbociclib and fulvestrant. Priority Review means the FDA will expedite its evaluation, aiming to make a decision in 6 months instead of the usual 10. This status is given to drugs that could significantly improve safety or effectiveness of treatment for a serious condition. The FDA’s decision (approval or not) is expected sometime in late 2024. It’s not approved yet as of this writing, but many in the oncology community are hopeful given the data. If approved, it likely will be indicated for postmenopausal HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer patients with a PIK3CA mutation, to be used in combination with endocrine therapy and a CDK4/6 inhibitor as initial therapy or after recurrence on adjuvant therapy. The EMA will likely consider it as well, possibly after U.S. approval.

Expected efficacy:

If inavolisib is approved and rolled out, patients with PIK3CA-mutant cancers could expect a substantial extension of their first remission period. Median PFS of 15 months in the trial means half the patients went longer than that without progression, which is encouraging. Some patients might have a year and a half or 2 years of disease control before needing to change therapy. While these numbers are from clinical trials (which have selected patients and close monitoring), they give a sense that this triple combination could become one of the most potent regimens for HR+ breast cancer. It addresses a key unmet need: previously, by the time we used PI3K inhibitors (like alpelisib), the cancer had already demonstrated resistance to multiple treatments. Now we might use a PI3K inhibitor earlier to forestall that resistance. The trade-off is that it’s a lot of medications at once – three cancer drugs – but if tolerated, the payoff in control time is significant.

Side effects:

Inavolisib’s side effect profile is similar to alpelisib’s, since they hit the same pathway, though detailed data from INAVO-120 hasn’t been fully published yet. Common side effects likely include hyperglycemia (high blood sugar), skin rash, and possibly diarrhea – hallmark toxicities of PI3K inhibitors. With alpelisib, for instance, many patients require diabetes medications temporarily to manage blood sugar, and prophylactic antihistamines to reduce rash occurrence. We can expect that oncologists will use similar tactics with inavolisib. One hope is that inavolisib might be more selective (it was designed to be a specific PI3Kα inhibitor with possibly fewer off-target effects) and thus might cause slightly fewer side effects, but one should be prepared for similar challenges. In the trial press releases, they noted the safety was manageable, but we’ll know more specifics when the data is fully presented. Patient monitoring will include regular glucose checks (especially in the first weeks), rash checks, and possibly stool habit questions. Combining with palbociclib and fulvestrant adds in palbo’s known side effects (low blood counts, mainly neutropenia, and fatigue). Actually, managing three drugs will require careful dose adjustments: for example, if a patient has low white cells from palbo and high sugar from inavolisib, the oncologist might juggle doses or supportive meds to keep everything in balance. The encouraging thing is that in the trial, patients were able to stay on therapy long enough to see the benefits, implying side effects were manageable with medical support. From prior experience, the key with PI3K inhibitors is to anticipate and manage side effects proactively (dietary changes to control blood sugar, skin moisturizers and antihistamines to prevent rash, etc.).

Comparison to standard of care:

The current standard first-line for HR+ mBC without considering this drug is an aromatase inhibitor + a CDK4/6 inhibitor (for example, letrozole + palbociclib). In INAVO-120, they used fulvestrant (instead of an AI) with palbociclib, likely because many patients had recurred quickly after AI in adjuvant or had AI resistance. Fulvestrant + palbociclib is a reasonable first-line alternative if a tumor is known to be resistant to AI. So the control was a standard-like regimen, and adding inavolisib made it much better for mutated cancers. If approved, this triple combo would become a new specialty first-line option for PIK3CA-mutant cases. Doctors will need to test patients for PIK3CA mutations at the time of metastatic diagnosis (often done via a blood test for circulating tumor DNA or a tumor biopsy). If positive, instead of just doing the typical two-drug combo, they might recommend a three-drug regimen. It’s somewhat analogous to how HER2-positive cancers get a triple combo (Herceptin + Pertuzumab + chemo) up front – here HR+ PI3K-mutant would get endocrine + CDK + PI3K inhibitor up front. If a patient doesn’t have the mutation, they wouldn’t use inavolisib because it likely wouldn’t help and would just add toxicity. So it’s a tailored approach. Compared to alpelisib (the older PI3K inhibitor), the difference is setting and combination: alpelisib is approved for use after at least one line of therapy (with fulvestrant) and isn’t typically combined with CDK4/6 inhibitors (studies of triple combos with alpelisib had more side effects). Inavolisib might be the PI3K inhibitor that successfully integrates into first-line triple therapy. That said, if a patient can’t tolerate inavolisib or doesn’t have access, the sequence would remain AI+CDK, then alpelisib+fulvestrant later. We’ll have to see if head-to-head comparisons or real-world data suggest one PI3K inhibitor is more tolerable than the other. From a patient perspective, taking three medications for cancer versus two is a consideration – more pills and possibly more expense (insurance coverage will be important). But if it delays IV chemo or another progression by a significant margin, many will find it well worth it.

Patient perspective:

Let’s consider a real-world scenario. Dana is a 55-year-old whose metastatic HR+ breast cancer is found to have a PIK3CA mutation. Her oncologist offers a clinical trial of inavolisib with palbociclib and fulvestrant. She’s a bit nervous about the side effects after reading about Piqray (alpelisib). During the first cycle, her blood sugar does go up – she’s put on a diabetes pill temporarily and meets with a nutritionist to cut down carbs and sugar in her diet. She also develops a mild rash on her arms; her care team quickly gives her an antihistamine and a topical steroid cream, which clears it up. After that, things stabilize. Three months in, her scans show significant tumor shrinkage. Six months in, still no new growth. She’s relieved: “I’ve basically been living a normal life – working remotely, walking my dog – and my scans look better than before. The side effects were real, but we managed them. I feel like I bought a lot of extra time on this treatment before I have to worry about the next step.” Dana’s story exemplifies the trade-off: diligent management of side effects can make a highly effective regimen tolerable. For patients and families, hearing that a combination has a 57% reduction in the risk of progression is encouraging, but one has to be prepared to put in the work to manage the treatment. Oncologists often say to their patients, “We have to be partners in your care,” meaning patients should promptly report symptoms and adhere to supportive measures so that these cutting-edge treatments can be given safely. If inavolisib gets approved, it will be another tool in the arsenal, allowing more patients to follow in the footsteps of those trial participants who enjoyed longer control of their disease.

Eftilagimod Alpha (EDP-202): Rallying the Immune System with Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has been a buzzword in cancer treatment for a while, but for breast cancer its impact has been limited. Classical immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors (like pembrolizumab/Keytruda) have shown benefit mainly in triple-negative breast cancer, and even then only in tumors that express certain immune markers (PD-L1). The more common HR-positive breast cancers tend to be less “visible” to the immune system – they don’t provoke a strong immune response, and thus drugs that simply take the brakes off immune cells haven’t worked as well. Eftilagimod alpha (IMP321), also known as EDP-202, is an innovative approach to immunotherapy in breast cancer. Rather than taking the brakes off T-cells (like PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors do), eftilagimod actively stimulates the immune system. It’s a protein that binds to a receptor called LAG-3 on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells. By doing so, it boosts the activation of T cells – essentially acting as an immune adjuvant or accelerator. Because of this mechanism, it’s termed a soluble LAG-3 protein and an MHC class II agonist (since it interacts with MHC II on dendritic cells). The strategy is to use eftilagimod in combination with other therapies (like chemotherapy) to turn a “cold” tumor (one that the immune system is ignoring) into a “hot” tumor (one that the immune system is attacking).

In metastatic breast cancer, eftilagimod is being studied in HR-positive patients in combination with weekly paclitaxel chemotherapy. Paclitaxel is a standard chemo for breast cancer that can kill cancer cells and also might have some immune-stimulating side effects (it can cause the release of tumor antigens, etc.). The trial program known as AIPAC (Active Immunotherapy PAClitaxel) has tested whether adding efti to paclitaxel improves outcomes.

How it helps:

Earlier, a phase IIb trial called AIPAC tested eftilagimod + paclitaxel vs placebo + paclitaxel in HR+ metastatic breast cancer patients who had progressed after endocrine therapy. That trial did not meet its primary endpoint of improving progression-free survival (the difference in PFS was not statistically significant). At first glance, that was disappointing. However, there were some encouraging signals: the combination appeared to be very safe and showed a trend towards improved overall survival (OS). In fact, final results reported a +2.9 month median OS improvement in the efti group compared to chemo alone, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. In other words, patients lived nearly 3 months longer on average with the immune booster, but the data wasn’t clear-cut enough to count as a proven benefit. Despite not hitting the mark on PFS, researchers noted that efti was doing something to the immune system as expected (patients had the desired immune responses in blood tests), and it had an “excellent safety profile”. They also noticed some patients did exceptionally well.

Rather than abandon the drug, the company (Immutep) refined their approach. They initiated a new phase II/III trial called AIPAC-003, focusing on a slightly different population (including HER2-low, HR+ patients) and potentially optimizing dosing. In early 2024, they released safety lead-in results from AIPAC-003: among the first 6 patients treated with eftilagimod 90 mg plus weekly paclitaxel, there were no serious side effects observed. Even more exciting, 50% of those patients (3 out of 6) had an objective response – meaning their tumors shrank significantly (2 partial responses and 1 complete response where the tumor became undetectable). The other 3 patients had stable disease, so all 6 had disease control (no progression). This 100% disease control rate in a small group is very promising, especially since these patients had cancers that had already progressed on available endocrine therapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors. Essentially, they were running out of good options, and yet half of them saw their tumors shrink on this new regimen. One patient’s tumor even disappeared on scans (complete response). While it’s a tiny sample and very early data, it gives hope that with the right approach, stimulating the immune system can help even in HR+ breast cancer.

The rationale is that paclitaxel plus efti might work in synergy: paclitaxel kills some tumor cells and possibly releases antigens, and efti rallies T-cells to attack any remaining cancer. There’s also interest in using efti alongside other immunotherapies. For example, could efti make “cold” tumors visible enough that a PD-1 inhibitor might then work? Those studies might come in the future.

Approval status:

Eftilagimod alpha is still investigational. It does not have FDA or EMA approval yet for any indication. It has been studied not only in breast cancer but also in some trials for lung cancer and head & neck cancer combined with PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors, where some encouraging results were also seen. For breast cancer, the path to approval would be a successful phase III trial demonstrating a clear benefit. The ongoing AIPAC-003 trial is aimed at that; if it shows significant improvement in survival or PFS, that could lead to regulatory filings. As of now, patients can only access efti through clinical trials. The FDA and EMA have recognized it as a novel approach, but they will require solid evidence of efficacy to approve it. Immutep, the company, often updates trial progress in press releases, and there is cautious optimism but nothing guaranteed. It’s a reminder that in drug development, sometimes initial trials miss the mark, but further research can salvage a drug if there’s enough reason to believe in it.

Expected efficacy:

It’s too early to quote definitive numbers for efti’s efficacy – we mostly have that one larger trial (which didn’t show PFS benefit) and early numbers from the new trial. If AIPAC-003 succeeds, we might see improvements in overall survival on the order of a few months or more. Importantly, immunotherapy responses can sometimes be long-lasting in a subset of patients. For instance, if the immune system gets properly engaged, some patients might experience very durable control even after stopping the drug (this has been seen with other immunotherapies in different cancers). So one hope is that efti could induce a more long-term immune surveillance against the cancer. Right now, expected efficacy might be “improved response rates” (meaning more tumors shrink) and hopefully improved survival, without necessarily a big impact on PFS early on. It might be that some tumors don’t shrink immediately but patients still benefit through slower growth due to immune pressure. These nuances are why PFS wasn’t improved before – immune therapy sometimes doesn’t show its benefit until later. For a patient, what this means is: if efti works for them, they could see their tumors shrink or stay stable and potentially live longer because their body is helping fight the cancer. And they’d achieve that without adding a lot of extra toxicity on top of chemo.

Side effects:

One of the most attractive aspects of eftilagimod is its mild side effect profile. In trials so far, it has not shown the kind of autoimmune side effects that PD-1 or CTLA-4 checkpoint inhibitors can cause (like colitis, hepatitis, etc.). It’s more of an immune stimulator than an immune unleasher, so it seems to avoid triggering the body to attack itself. The AIPAC trials reported no serious treatment-related adverse events with the 30 mg dose in earlier studies, and none with 90 mg in the recent lead-in. “Treatment-emergent adverse effects” were mild. Typical side effects observed have been things like injection site reactions (since efti is given via injection, similar to an insulin shot under the skin), maybe mild fevers or fatigue as the immune system gets revved up occasionally – akin to how one might feel after a vaccine. But compared to traditional chemo side effects, efti doesn’t add much burden. In fact, patients might not even be sure if they’re getting efti or placebo in a blinded trial, because it doesn’t usually cause obvious symptoms.

When combined with paclitaxel, most side effects people experience are from the chemo (hair loss, neuropathy, lowered blood counts). The good news is that adding efti did not make those any worse than expected in the trial. This synergy of high efficacy signals with low additional toxicity is somewhat rare and is what makes people excited about efti. If it works, it could improve outcomes without making patients feel sicker – a huge win in the metastatic setting where quality of life is crucial.

Comparison to standard of care:

For HR-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after hormonal therapies, the standard next step is chemotherapy. Paclitaxel is one common choice. If efti proves itself, the new standard could become paclitaxel + efti instead of paclitaxel alone. Think of it like how, in some cancers, chemo-immunotherapy combos have replaced chemo alone (e.g., lung cancer often uses chemo + immunotherapy now). This would be analogous – an immunotherapy added to chemo for HR+ breast cancer. If a patient’s cancer is HER2-low and HR+, nowadays an option is also trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu) as we discussed. So an oncologist might have to decide: do we try Enhertu or do we try paclitaxel+efti? It may depend on factors like how much HER2 expression, how much immune infiltration is in the tumor (there’s some evidence that efti works better in patients with certain immune profiles), and patient preference. It could also be sequenced – one after the other. The key point is efti could enrich the toolbox for that scenario where endocrine options are exhausted. Another area of need is triple-negative breast cancer; interestingly, efti hasn’t been heavily tested there because other immunotherapies existed, but one could consider it in the future.

Importantly, efti could potentially be combined with other therapies too. For example, could you add efti to an existing regimen like capivasertib + fulvestrant to try to induce immune attack? Or to other chemos like capecitabine? Those are speculative ideas. But for now, paclitaxel + efti is the focus, because paclitaxel can be immunogenic. Compared to checkpoint inhibitors (like Keytruda, which is used in PD-L1 positive triple-negative breast cancer), efti is a different mechanism. One day, maybe both could be used together for an even stronger effect (some trials in other cancers are combining efti with pembrolizumab).

Patient perspective:

Elaine, a metastatic breast cancer patient in her late 60s, had been through multiple lines of hormone therapy and targeted drugs over 5 years. Her cancer recently started growing again, and her oncologist recommended chemotherapy. Elaine was worried about chemo side effects and the feeling that options were running out. She was offered a clinical trial with paclitaxel + an “immune booster” (which was efti). She thought, “Why not try it? If it might make the chemo work better without making me feel worse, I’m in.” After starting treatment, Elaine lost some hair and felt the usual fatigue from weekly Taxol, but she noticed she didn’t feel significantly worse than a friend of hers who’d gone through Taxol without efti. After a few months, her CT scans showed that some of her tumor spots had shrunk by 30%, and the rest were stable – good news that the treatment was working. She also found out she was one of the patients getting the actual efti (not placebo), and she was glad: “I like the idea that we’re waking up my immune system. It makes me feel like my body is fighting back, not just the drug.” Elaine continues on therapy, and at her last check, there’s no new growth. She’s hopeful she can stay on this regimen for as long as it keeps the cancer at bay.

It’s stories like this, mirrored by some real trial patients, that illustrate the potential of eftilagimod. One complete responder in the trial experienced her cancer vanishing on scans, which is unusual in this late-line setting – that gives hope that a fraction of patients might get exceptional benefit. Even those who don’t have such dramatic responses could still gain extra time without progression. And given how gentle efti is side-effect-wise, it largely preserves quality of life during that time. That balance of optimism and practicality is key: efti is not a magic bullet that will cure metastatic breast cancer, but it could practically extend life and meaningfully boost the effectiveness of conventional treatments while keeping patients feeling relatively well.

Conclusion: A Future Bright with Hope and Realism

Metastatic breast cancer remains a tough diagnosis, but the therapeutic landscape is rapidly evolving. The new therapies discussed – capivasertib, trastuzumab deruxtecan, camizestrant, inavolisib, and eftilagimod – each attack the cancer from a different angle. They aim to outsmart the cancer’s tricks: blocking escape pathways, delivering drugs directly into cancer cells, degrading mutant receptors, targeting driver mutations, and rallying the immune system. For patients and caregivers, these advances translate into more options and more time. As Dr. Mortimer comforted her patient, even though mBC is considered terminal, “40% of stage 4 patients live 8 years or longer” now – a statistic that is improving as new treatments emerge. The goal is to transform mBC into a disease that people can live with for many years while maintaining good quality of life.

It’s important to maintain realistic expectations: each of these therapies can have side effects, and not every patient will benefit the same way. Cancer can be clever and may eventually find a way around even the newest drug. But where one therapy stops working, another may step in. The tone in oncology today is cautiously optimistic. We are seeing patients live longer than before, turning what used to be a few years prognosis into many years for some. Clinical trial participants, like those we’ve mentioned, often say they choose to join trials not only for themselves but to help improve treatment for the next person. Their courage has led to FDA approvals that now benefit thousands.

For patients and caregivers reading this: hope is justified, grounded in real progress. At the same time, it’s wise to be informed about the practical aspects – the need for genetic testing of the tumor to find the right targeted treatments, the importance of reporting side effects early to manage them, and the reality that these drugs control the disease rather than cure it. Many metastatic breast cancer patients echo Sabrina’s sentiment: “I know I can’t be cured. I live with it. It’s part of me, but not the whole me.”. With each new therapy, that part of you – the cancer – becomes a smaller part of you, while the rest of your life grows larger. You can plan for the future even as you deal with treatment in the present.

In summary, new therapies for metastatic breast cancer are providing fresh hope and tangible benefits: longer control of the disease, new chances after old options run out, and even stories of dramatic responses that buy precious time. The road of metastatic breast cancer is still challenging, but it’s no longer as dark and unyielding as it once was. Research is lighting the way, and patients are living proof that it’s possible to continue living fully with metastatic cancer. As one survivor put it, “People are living longer after being diagnosed with mBC… I’m going through some things, but I’m living”. The blend of hope and realism is perhaps best captured by that outlook – acknowledging the difficulties, but embracing the life that still lies ahead. With these new therapies, we strive to turn every extra month into a milestone and every year into a celebration of resilience and innovation.

Sources:

- Turner NC, et al. (2023). Capivasertib plus fulvestrant vs placebo plus fulvestrant in AI-resistant HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer (CAPItello-291). New England Journal of Medicine. – Key trial showing capivasertib improved progression-free survival

- FDA News Release – FDA approves capivasertib with fulvestrant for breast cancer (Nov 16, 2023). – Approval details for capivasertib in the US, including indication for tumors with PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN mutations

- Modi S, et al. (2022). Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. – DESTINY-Breast03 trial results; Enhertu vs T-DM1 efficacy

- FDA News – Enhertu approved for HER2-low metastatic breast cancer (Aug 2022). – Result of DESTINY-Breast04 leading to approval in HER2-low disease; nearly doubled PFS

- Hurvitz SA, et al. (2021). Trastuzumab deruxtecan for HER2+ metastatic breast cancer. ESMO Congress Presentation. – Noted risk of interstitial lung disease with Enhertu and management

- Kalinsky K & Mayer EL. (2024). OncLive Insights: SERENA-2 trial of camizestrant vs fulvestrant. – Camizestrant showed improved PFS, especially in ESR1-mutant cancers; side effects like mild nausea, rare visual issues (phosphenes), and low heart rate were noted (Link)

- Hope S. Rugo, MD – SABCS 2022 Highlights (2023). – Discussion of new oral SERDs and their emerging role; camizestrant and others anticipated to expand options

- Ryan CJ. (2024). OncLive News: Inavolisib + Palbociclib/Fulvestrant receives FDA Priority Review. – Phase III INAVO-120 data: inavolisib triple therapy reduced risk of progression by 57%, median PFS 15 vs 7.3 months

- Immutep Ltd. Press Release (2024). – AIPAC-003 trial update: Eftilagimod + paclitaxel in HR+/HER2-low mBC showed 50% response rate in initial patients, with 1 complete response; good safety profile

- Guido Kroemer, et al. (2023). Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer – Final AIPAC phase IIb results. – Eftilagimod with paclitaxel showed a nonsignificant +2.9 month median overall survival trend and confirmed immune activation without added toxicity

- Patient Stories – Breast Cancer Research Foundation & City of Hope. – First-person accounts (Tiffany and Sabrina) illustrating life with metastatic breast cancer and the impact of new treatments like Enhertu

- Expert Commentary – City of Hope article. – Quote: “Forty percent of Stage 4 patients live 8 years or longer… And many new therapies are coming.” – highlighting improved outlook